McGregor, SLT (2003) "Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence." Kappa Omicron Nu Human Sciences Working Paper Series. Retrieved from https://www.kon.org/hswp/archive/consumerism.html | local copy (html)

-

"Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence" is also available via the Canadian Fair Trade Network (CFTN.ca) | pdf (online) local copy (pdf)

-

See also:

-

McGregor SLT (2010) "Consumer Moral Leadership." | chapters 1-2 [local copy, pdf]

-

McGregor, S.L.T. (2006-05). "Reconceptualizing risk perception: Perceiving Majority world citizens at risk from 'Northern' consumption." International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(3): 235-246. | local copy (pdf)

-

McGregor SLT (2006-03) "Understanding consumers' moral consciousness." International Journal of Consumer Studies. 30(2): 164-178. | local copy (pdf)

-

Author: Dr. Sue L.T. McGregor, Ph.D.

Professor Emerita

Coordinator, Undergraduate Peace and Conflict Studies Program

Mount Saint Vincent University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada

Publication Date: 2003

Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence

McGregor, SLT (2003) "Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence." Kappa Omicron Nu Human Sciences Working Paper Series. Retrieved from https://www.kon.org/hswp/archive/consumerism.html [html; local copy (html)] | pdf [local copy (pdf)]

Abstract

Capitalistic consumerism needs an infrastructure in order to continue to manifest itself. Components of that infrastructure include technology and telecommunications, corporate led globalization, the neo-liberal market ideology, world financial institutions, and complacent, or complicit, governments. Most significantly, the other component of this infrastructure is the consumer, and by association, the family and consumer sciences (FCS) profession. The basic premise of this paper is that this entire infrastructure is a key source of structural violence, enabled by consumers and FCS professionals who, knowingly or unknowingly, embrace the ideology of consumerism.

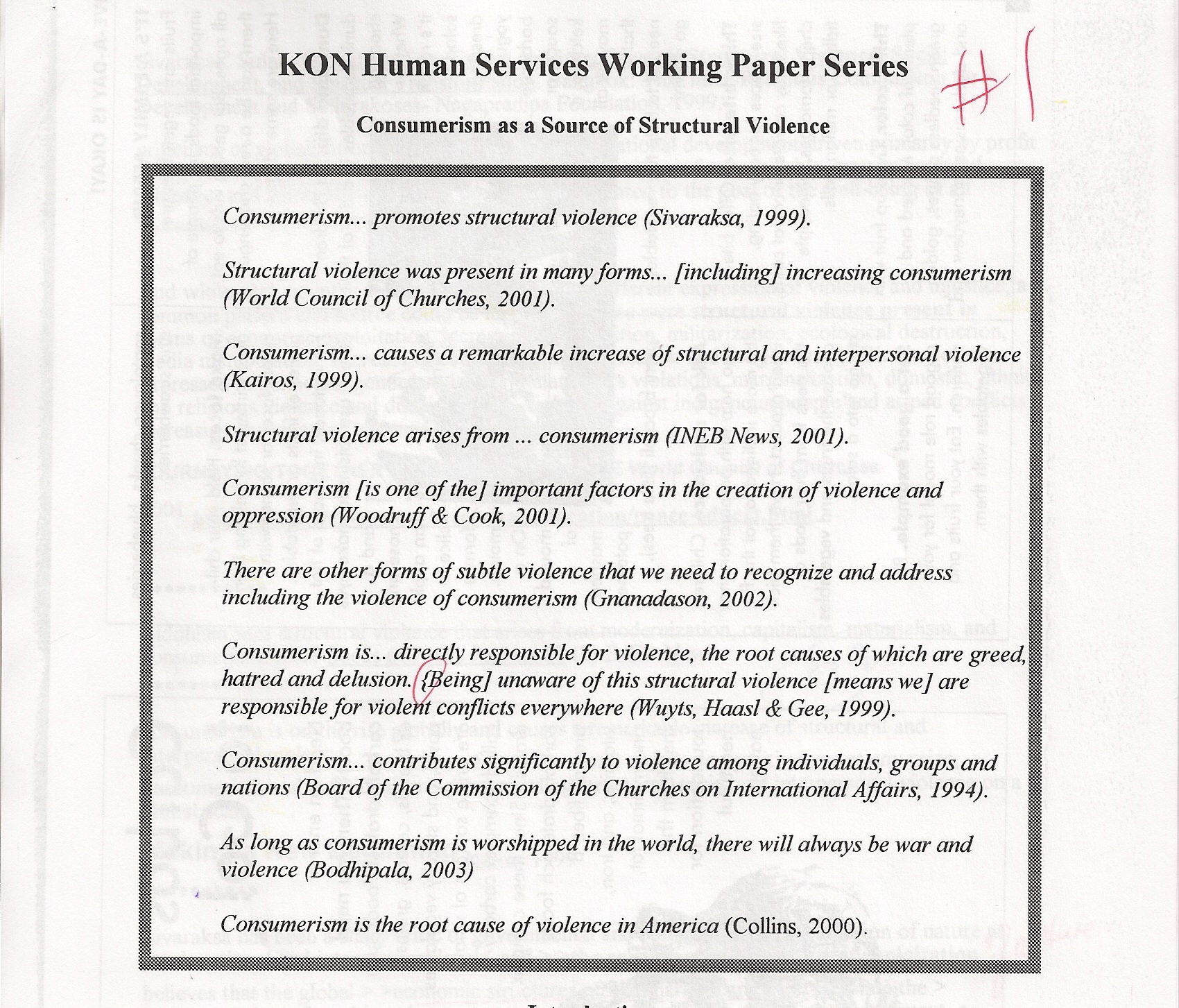

- Consumerism ... promotes structural violence.

- Structural violence was present in many forms ... including increasing consumerism.

- Consumerism ... causes a remarkable increase of structural and interpersonal violence.

- Consumerism is one of the important factors in the creation of violence and oppression.

- There are other forms of subtle violence that we need to recognize and address including the violence of consumerism.

- Consumerism is ... directly responsible for violence, the root causes of which are greed, hatred and delusion. Being unaware of this structural violence means we are responsible for violent conflicts everywhere.

- Consumerism ... contributes significantly to violence among individuals, groups and nations.

- As long as consumerism is worshipped in the world, there will always be war and violence.

- Consumerism is the root cause of violence in America.

- It is universally recognized that ... consumption problems cause countless violence.

[Click image to open in new window.]Image source; Author Sue McGregor, pers. comm., 2020-07-13:

I attached my original text box from my first draft with quotes assigned to people:

-

Sivaraksa S. (1999) "Global Healing: Essays and Interviews on Structural Violence, Social Development and Spiritual Transformation." Wisdom Books.

-

World Council of Churches (2001) "Networking in peace education." [local copy (html)]

-

INEB News (2001) "Seeds of Peace Journal. 17(2):51. [local copy" (pdf) | local copy (pdf, pp. 1, 51 only)]]

-

Woodruff A & Cook L (2001) "Final document of the Presbyterian Consultation on Violence" [http://www.pcusa.org/missionconnections/letters/woodruffa_0107violence.htm]. Louisville, KN: General Assembly Mission Council. [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (html, from 2004-12-22 Internet Archive capture)]

-

Gnanadason, Aruna (2002-05) "Religion and Violence as a Challenge to the Ecumenical Movement" [http://www.nccindia.org/review/article%202.htm]. National Council of Churches Review, 122/4: 421-435. [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (html, from 2005-02-05 Internet Archive capture)]

-

Cited in: pdf (pdf).

-

-

Wuyts A, Hassl E, & Gee D (1999) "Religions: Do they help or hinder?" [http://www.quaker.org/qcea/ae215.htm]. Bruxelles, Belgium: Quaker Council for European Affairs. [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (html, from 2005-02-15 Internet Archive capture)]

-

Bodhipala B (2003) "Buddhism: A Panacea For "Violence and World Disorder"." Mumbai, India: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavans. [local copy (html)]

-

Collins??? [ << COMMENT (BuriedTruth): perhaps, Carter M (1999), cited in "Consumerism as a Source of Structural Violence"?]

Also, see below (from another paper):

-

Excerpt from: McGregor, S.L.T. (2007) "Consumerism, the common good and the human condition." Journal of Family and Consumer Sciences, 99(3): 15-22.

-

Consider these facts. They provide evidence that consumerism is not good for the common good, at least not how it is lived out in the daily lives of the one billion people comprising the consumer society:

-

Even though Northern consumers (Western and European) comprise just more than 20% of the world's population, they consume more than 86% of the world's resources to support their consumer society. They have 87% of all cars, hold 74% of all phone lines, use 84% of all paper, consume 58% of all energy, eat 45% of all fish and meat, and get 94% of all bank loans. This means that eight people out of 10 in a room are left with only a 14% share of global consumption activities. This fact represents a great divide in power.

-

Total global consumption levels exceeded the planet's ecological capacity in the late 1970s. We would need more than five planet Earths to sustain the world if we all consumed at the level of just two countries, the US and Canada. What is even more telling is that citizens of these two countries are the least likely to pay more for organic, environmentally friendly or fair trade products.

-

The Western world spends more on luxury products, such as cruises, perfume, makeup, and ice cream (let alone necessities), than it would take to achieve the UN's Millennium Development Goals (dealing with poverty, literacy, hunger, child and mother mortality, environmental sustainability, gender equality and empowerment, and disease).

-

By some estimates, 83 percent of all clothing purchased in North America is made somewhere else, as are 80 percent of the toys, 90 percent of the sporting goods, and 95 percent of the shoes. Often, less than 1 percent of the final cost of a product is paid to the worker, who makes, on average, 15-25 cents US per hour.

-

The entire consumer infrastructure is a key source of structural violence, and is enabled by consumers who, knowingly or unknowingly, embrace the ideology of consumerism. Nearly 40% of all clothes and apparel sold in North America are made in China, where workers are forbidden to organize to improve work conditions (sweatshops, child labour, prison labour). Even if people wanted to consume more fairly, less than .01 percent of world trade is in the form of fair trade. The system precludes consuming differently.

-

A full 80 percent of all products purchased in Northern countries are made by women (on average aged 12-14). Typical sweatshop employees, 90 percent of whom are women, are young and uneducated (between the ages of 16-25). It is estimated that, of the 2.2 billion children in the world, nearly 250 million children in developing countries work in sweatshops (Global Market Insite, 2005; McGregor, 2006a; New Community Project, 2005; UNESCO, 2002; Woolf, 2001; Worldwatch Institute, 2004).

-

-

Global Market Insite (2005). "Consumer polls" [http://www.gmi_mr.com/gmipoll/docs/wave14/Q287.pdf]. [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (pdf, from 2007-10-28 Internet Archive capture)]

-

McGregor, S.L.T. (2006a). "Reconceptualizing risk perception: Perceiving Majority world citizens at risk from 'Northern' consumption." International Journal of Consumer Studies, 30(3), 235-246. | local copy (pdf)

-

New Community Project. (2005). "No sweat! Taking action to end sweatshops" [http://www.newcommunityproject.org/no_sweat.shtml] [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (html, from 2010-04-18 Internet Archive capture)]

-

UNESCO (2002). "Teaching and learning for a sustainable future." [<< the format of page at original link has changed over the years (<<link to Internet Archive). The original "Teaching and learning for a sustainable future" URL (far left) now, 2020-07-13, redirects to UNESCO's "Education transforms lives" website.]

-

Woolf L (2001) "Women and sweatshops" [http://www.webster.edu/~woolflm/sweatshops.html]. [<< dead (404) link; not found in Google, 2020-07-13 | local copy (html, from 2015-04-24 Internet Archive capture)]

-

Worldwatch Institute (2004). "State of the World 2004: The consumer society." London: W.W. Norton & Company. [local copy (pdf)]

-

Sue L. T. McGregor, PhD, Professor

Docentship in Home Economics, University of Helsinki

Marjorie M. Brown Distinguished Professor

Doctoral Program Coordinator, Chair IDAC

Faculty of Education, Seton 535

Mount Saint Vincent University

166 Bedford Highway, Halifax NS B3M 2J6 Canada

New Book: Transversity (With Russ Volckmann)

New Book: Consumer+Moral+Leadership"+mcgregor">Consumer Moral Leadership

Professional Website: McGregor Consulting GroupWith knowledge comes responsibility.

Please consider the environment before printing this e-mail -

Introduction

This collection of quotes is not from the family and consumer sciences (FCS) literature. The quotes are definitely not from the consumer studies literature. They are from the peace and social justice literature. If readers are anything like me, perceiving consumerism as a form of structural violence will be unfamiliar and uncomfortable. It is not the way the profession has traditionally viewed or understood the widespread and popular concept of consumerism, central to our field of study. Seeing consumerism as violence turns everything on its head. My hope is that this working paper will lead people out of their comfort zone so they can enter into a collective discussion about consumerism as a source of structural violence.

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Consumerism

Consumerism is usually understood to refer to the social movement that seeks to protect the consumer against excesses of business and promote the rights of consumers (Gabriel & Lang, 1995). People in this movement often fight for the rights of consumers who are affected by structural violence (landlord tenant issues, housing discrimination, abuse of elderly consumers, discrimination against women by financial institutions, and children as vulnerable consumers). Although much as been written on consumerism as a social movement that arose as a result of consumer problems caused by the way the market is structured, little has been written in the family and consumer sciences (FCS) field about consumerism as a source of structural violence.

For the sake of the argument presented in this working paper, consumerism is viewed as a facet of the ideology of contemporary capitalism. ...

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

A consumer society has the following characteristics (drawn from McGregor, 2001). Identities are built largely out of things because things have meaning. People measure their lives by money and ownership of things. People are convinced that to consume is the surest route to personal happiness, social status, and national success. Advertising, packaging, and marketing create illusory needs that are deemed real because the "economic" machine has made people feel inferior and inadequate. To keep the economic machine moving, people have to be dissatisfied with what they have, hence, with whom they are. Consequently, the meaning of one's life is located in acquisition, ownership, and consumption.

In a consumer society, market values permeate every aspect of daily lives. Marketplaces are abstract, stripped of culture (except the culture of consumption), of social relations, and of any social-historical context. Consumers are placed at the center of the "good society" as individuals who freely and autonomously pursue choices through rational means, creating a society through the power they exercise in the market. Consequently, in a consumer society, there is a widespread lack of moral discipline, a glorification of greed and material accumulation, an increased breakdown in family and community, a rise of lawlessness and disorder, an ascendancy of racism and bigotry, a rise in the priority of national interests over the welfare of humanity, and an increase in alienation and isolation. Social space is reorganized around leisure and consumption as central social pursuits and as the basis for social relationships. A consumer society needs leisure to be commercialized and the home to be mechanized in order that time and energy are freed up for shopping and producing more things to buy. Social activities and emotions are turned into economic activities through the process of commodification. ...

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Consumerism is the misplaced belief (myth) that consuming will gratify the individual. In this sense, it is an acceptance of consumption as a way to self-development, self-realization, and self-fulfilment. In a consumer society, an individual's identity is tied to what she or he consumes. People buy more than they need for basic subsistence and are concerned for their self-interest rather than for mutual, communal, or ecological interest. In a consumer society, whatever maximizes individual happiness is considered the best action and that line of thinking gets translated into accumulating goods and using more services (Goodwin, Ackerman & Kiron, 1997). Society has even gone so far as to understand consumerism to be a vehicle for freedom, power, and happiness. It supplements work, religion, and politics as the main mechanism by which social status and distinction are achieved. Although people perceive each of the isolated (a) personal moments of consumption, (b) working within the home, and (c) engaging in cultural endeavors as very private, they are actually very public actions, inherently tied to global economic and political processes.

In the global marketplace, consumerism is also viewed as the pursuit of ever-higher standards of living, thereby justifying global development and capitalism via trade and internationalism of the marketplace. Capitalism needs laborers, money, and markets. Large sections of the world population are excluded in a consumer society, save for the exploitation of their labour and their nation's natural resources to produce consumer goods. Rampant consumerism has lead to pollution, hazardous wastes, exhausted resources, irreversible environmental damage, spiritual withdrawal, and an increased gap and growing tension between the haves and have-nots. The loss of biodiversity is paralleled by the loss of cultural diversity via cultural homogenization, leading to the consumer monoculture that feeds the capitalistic machine.

"Under the spell of consumerism, few people give thought to whether their consumption habits produce class inequality, alienation, or repressive power, i.e., structural violence. People are concerned more with the "stuff of life" rather than with "quality of life," least of all the quality of life of those producing the goods they consume. Indeed, consumerism is manifested in chronic purchasing of new goods and services with little attention to their true need, durability, country of origin, working conditions, or environmental consequences of manufacture and disposal ("Why overcoming consumerism," 1997).

To conclude, capitalistic consumerism needs an infrastructure in order to continue to manifest itself. Components of that infrastructure include technology and telecommunications, corporate-led globalization, the neo-liberal market ideology, world financial institutions, and complacent, or complicit, governments. Most significantly, the other component of this infrastructure is the consumer, and by association, the family and consumer science profession

.The basic premise of this paper is that this entire infrastructure is a key source of structural violence, enabled by consumers who, knowingly or unknowingly, embrace the ideology of consumerism.

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Consumerism as Structural Violence

Johan Galtung (1969) first coined the term structural violence intending it to refer to the presence of justice (positive peace) to balance the prevailing focus on negative peace, the absence of war and violence. Whereas direct violence and war are very visible, structural violence is almost invisible, embedded in ubiquitous social structures, normalized by stable institutions, and regular experience. Because they are longstanding, structural inequities usually seem ordinary, the way things are and always have been done. Worse yet, even those who are victims of structural violence often do not see the systematic ways in which their plight is choreographed by unequal and unfair distribution of society's resources or by human constraint caused by economic and political structures.

Unequal access to resources, political power, education, health care, or legal standing are all forms of structural violence (Winter & Leighton, 1999). Structural violence can also occur in a society if institutions and policies are designed in such a way that barriers result in lack of adequate food, housing, health, safe and just working conditions, education, economic security, clothing, and family relationships.

People affected by structural violence tend to live a life of oppression, exclusion, exploitation, marginalization, collective humiliation, stigmatization, repression, inequities, and lack of opportunities due to no fault of their own, per se. The people most affected by structural violence are women, children, and elders; those from different ethnic, racial, and religious groups; and sexual orientation.

Those adversely affected by structural violence are not involved in direct conflict that is readily identifiable. Because they, and others, may not comprehend the origin of the conflict, they feel they are to blame, or are blamed, for their own life conditions.

This perception is readily escalated because people's perceptual and cognitive processes normally divide people into in-groups and out-groups. Those outside 'our group' lie outside our scope of interest and justice. They are invisible. Injustice that would be instantaneously confronted if it occurred to someone in 'our group' is barely noticed if it occurs to strangers or those who are invisible and irrelevant. Those who fall outside 'our group' are easily morally excluded and become demeaned or invisible, so we do not have to acknowledge the injustice they suffer (Winter & Leighton, 1999). 'Consumerism is the drug that causes people to fall into moral sleep and remain silent on all kinds of public matters. As long as their little world of peace and relative prosperity is not disturbed, they are happy not to get involved. It is against this background of consumer complacency that all kinds of moral relaxation can arise . . . . A consumer society is one that is prepared to sacrifice its ethics on the altar of the material 'feel-good' factor' (Benton, 1998).

Persons living in a consumer society live a comfortable life at the expense of impoverished labourers and fragile ecosystems in other countries. Too often, they conclude that they must arm themselves to protect their commodities and the ongoing access to them. This position justifies war and violence (Cejka, 2003). The 'veil of consumerism' enables them to overlook the connections between consumerism and oppressive regimes (governments, world financial institutions, and transnational corporations) that violate human rights, increase drug trade, and boost military spending (Sankofa, 2003). This disregard is possible because consumerism accentuates and accelerates human fragmentation, isolation, and exclusion for the profit of the few, contributing significantly to violence (Board of the Commission of the Churches on International Affairs, 1994). Society has ignored the 'new slavery' and the resultant disposable people through ignoring the implications of consumption decisions on third world citizens, the next generation, and those not yet born (Sankofa). ...

[ ... SNIP! ... ]

Return to Persagen.com