SOURCE: theIntercept.com, 2020-01-08

Record droughts, raging forest fires, crop failures, and disappearing glaciers: It has become undeniable that the planet is in the early stages of a climate crisis with dire implications. As terrifying as it is, this unfolding disaster has not come as a surprise to everyone -- especially not the people who have been profiting off fomenting the climate emergency.

It has come to light in recent years that major fossil fuel companies knew well in advance that their activities were gravely distorting the climate, even as they waged a relentless campaign to confuse public opinion and prevent regulatory action. A flood of cases are now making their way through the courts against Exxon Mobil and other companies accused of concealing the truth of a calamity now slowly enveloping the world.

Imperial Oil, Exxon's Canadian subsidiary, is a household name in Canada thanks to its ubiquitous Esso gas stations. Exxon owns 70 percent of the company, which is a major holder of reserves in the controversial Alberta oil sands. Like its parent company, Imperial has been accused of climate denialism and efforts to stall meaningful regulation needed to prevent today's crisis. In a 1998 article published in Imperial's in-house magazine, former Imperial CEO Robert Peterson wrote that there is 'absolutely no agreement among climatologists on whether or not the planet is getting warmer or, if it is, on whether the warming is the result of man-made factors or natural variations in the climate.' He added that 'carbon dioxide is not a pollutant but an essential ingredient of life on this planet.'

Peterson's paeans to the benefits of carbon dioxide notwithstanding, experts at his company knew with confidence not only that climate change was real, but also that Imperial's activities were causing crippling harm to the environment. That knowledge was recorded in company documents that were recently revealed to the public and reviewed by The Intercept.

-

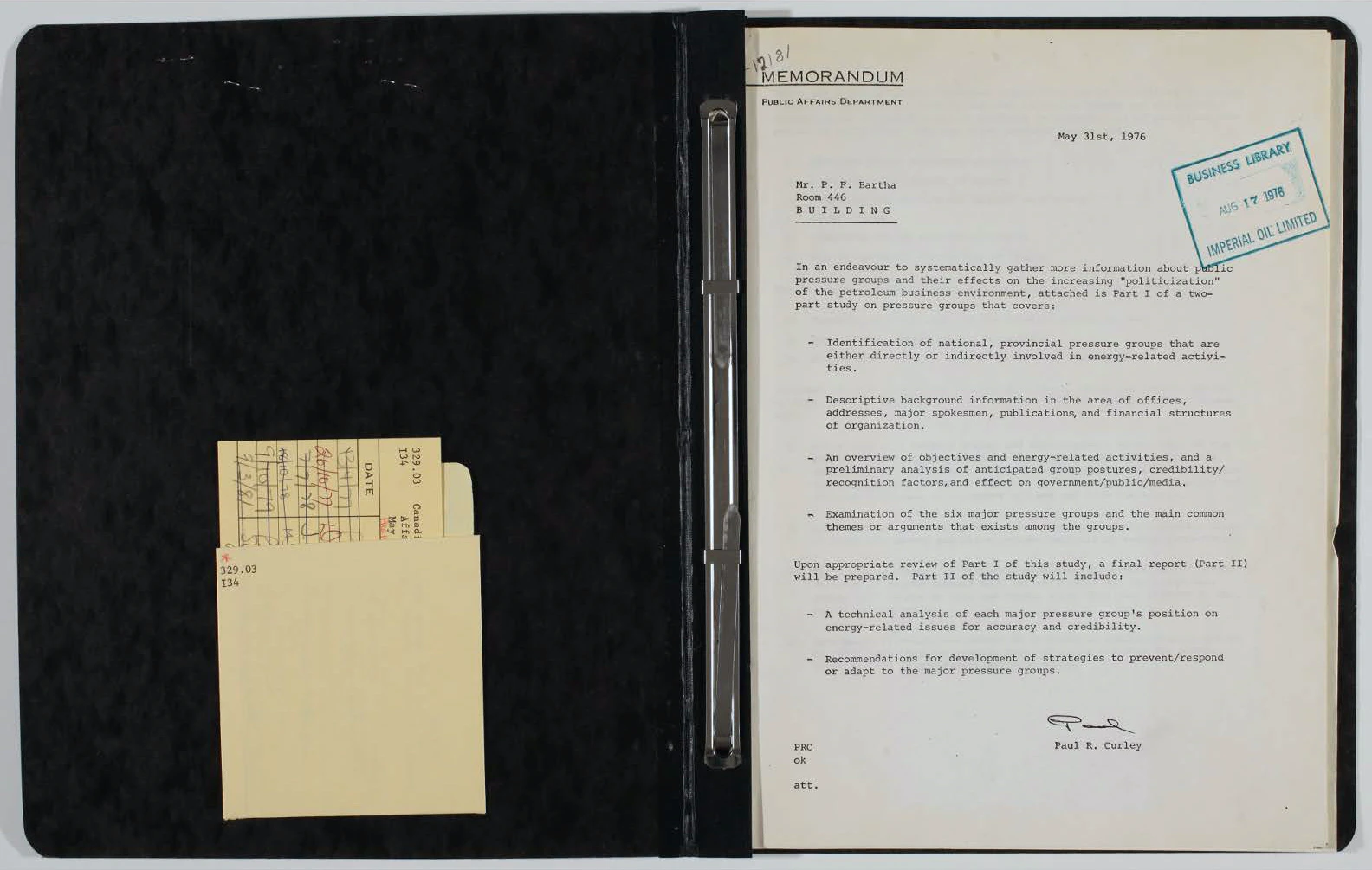

A portion of a report titled, "Canadian pressure groups, Part I, by Public Affairs Dept. Toronto, Imperial Oil Limited, May 1976."

[Image source. Click image to open in new window.]

The cache of documents shows that as far back as the 1960s, Imperial had begun hiring consultants to help them manage a future public backlash over its environmental record, as well as conducting surveillance on its public critics. The documents also show that, as the company began to accept the implications of a warming planet, instead of acting decisively to change its business model, it began considering how a melting Arctic might open up new business opportunities.

Even as the fossil fuel industry continued to fight against renewables in public and its CEO worked to confuse public opinion on this critical issue, in private Imperial's experts recognized the urgency of switching to sustainable energy.

All of this took place decades ago, when the climate crisis was still largely avoidable and its deadly contours had yet to take shape.

The documents providing details on Imperial's historical activities were retrieved from an archive in Calgary's Glenbow Museum by U.S.-based climate advocacy groups Desmog and the Climate Investigations Center. Available since 2006, the depth of the archive has never been fully examined, though previous reporting on documents from the Glenbow Museum revealed that Imperial made detailed plans for exploiting Arctic ice melt and that the company knew high carbon taxes would be required to stave off the effects of climate change decades ago -- even as it worked to ensure that they would not be put in place.

"Throughout the '70s and '80s, Exxon, and by extension Imperial, were among the leading researchers in the world on climate change," said Keith Stewart, a senior energy strategist with Greenpeace Canada and a lecturer at the University of Toronto. "They understood the science and understood the implications. They had a choice to either change their business model or obfuscate the reality. They chose to obfuscate. Long after they had accepted that climate change was real, and even started building their installations differently to reflect that, the company continued to publicly deny the science that they knew to be true."

The documents provide a disturbing insight into how Imperial grappled with the obvious environmental impact of its operations over the past several decades.

"Air pollution is an area highly charged with emotion and one characterized by a lack of data and rational guidelines," noted a 1967 report prepared by a consultant for Imperial and marked as "confidential." The report added that public opinion in the United States on the subject was "out of control."

That report, titled "Air/Water Pollution in Canada: a Public Relations Assessment," outlined possible consequences for Imperial if the public continued to pressure the company over its environmental record. The threats included "difficult-to-change anti-oil industry attitudes" and demands to switch to renewable energy. "Due to continuing exposure to stories in the mass media, the general public could easily be persuaded to support increased pollution regulation and legislation," the report warned. "It could be encouraged to support the electric car, nuclear energy and other technology favouring competitive fuels."

The report did not say that Imperial should do nothing in response to the devastating environmental consequences of its business, which had become clear as early as the 1960s. As a "responsible corporate citizen," Imperial would obviously aim to avoid harming Canada's environment and the health of its people. A public relations campaign aimed at pushing back against pressure on the company might serve as a means of buying time before more substantive steps could be taken, the report suggested. Such a campaign could help "keep public and legislative opinion in control so that increased pollution control measures affecting all corporate functions can proceed on an orderly, economic and reasonable basis."

Despite going on the PR offensive, by the 1970s, Imperial was becoming yet more alarmed by the growing public criticism of its activities. Its response to this perceived threat was typical of many powerful yet paranoid institutions: surveillance.

As public pressure mounted, Imperial began putting together dossiers on organizations that it accused of "politicization" of the fossil fuel business. A 1976 report titled "Canadian Pressure Groups," prepared by the company's public affairs department, offered detailed profiles of six Canadian NGOs alleged to have targeted the company over environmental or social issues. Among the information they gathered was financial data about the operations of these organizations, along with physical addresses and information about their key spokespeople.

The document claimed to provide "identification of national, provincial, pressure groups that are either directly or indirectly involved in energy-related activities," while indicating that a future study would look at "recommendations for development of strategies to prevent/respond or adapt to the major pressure groups."

As the environmental toll of its operations continued to build and public anger rose along with the damage, Imperial gradually began developing its own environmental research capacities. By the early 1990s, the company's in-house researchers had made some important findings: Not only was the Earth's climate being dangerously heated up by the emission of greenhouse gases, but Imperial's own operations were also playing a role in this potentially existential threat.

As the astonishing scale of the climate crisis slowly came into focus, the company began gaming out possible responses. Researchers at Imperial analyzed different ways of reducing the carbon footprint of energy production and gradually moving society as a whole toward renewables, including the possibility of underground capture and storage of carbon emissions, solar energy production, and electric vehicles.

Yet the company's leadership remained fixated on ensuring that whatever was done shouldn't be too much and, most important of all, that it shouldn't result in government regulation of Imperial's operations. A 1990 document, "Response to a Framework for Discussion on the Environment -- The Green Plan: A National Challenge June 1990," was published in the context of a high-level debate then taking place in Canada on developing a sustainable economy. In the document, Imperial warned that stakeholders in government and private industry should be careful to not "out-green each other." Any discussion of environmental controls must be carefully balanced with concerns about how regulating the oil industry might harm the Canadian economy, the report emphasized, calling for approaches to climate change that "rely as much as possible on the market means to provide economically appropriate information and incentives."

An assessment prepared by Imperial and published the following year conceded, "The simplest way to reduce CO2 emissions from energy is to substitute natural gas, nuclear and hydropower for coal." The report recognized that "a carbon tax causes the most direct impact on CO2 since the tax is in proportion to the emissions." Despite these admissions, Imperial continued low-balling estimates on what such a tax should look like, as reports by HuffPost and Bloomberg recently noted.

As the planet warmed and the long decline of glaciers accelerated, the company was also evidently using its environmental research to scope out new business opportunities afforded by climate change. "The fate of sea ice in a warmed planet will largely determine how Imperial operates in the Arctic," said one document from 1991, a report called "The Application of Imperial's Research Capabilities to Global Warming Issues." Exxon, Imperial's parent company, has had no qualms about capitalizing on the short-term economic opportunities offered by climate change either: The oil giant partnered on a new deal this October to use ice-breaking ships to transport liquified natural gas across the warming Arctic.

In the two decades since Robert Peterson, Imperial's former CEO, insisted that pumping carbon dioxide in the atmosphere is actually good for the environment, Imperial Oil continued to ramp up its fossil fuel production. According to its latest operating results, the company increased its extraction of barrels per day from 375,000 to 383,000 between 2017 and 2018. Imperial's current head, Rich Kruger, lauded the numbers, stating that Imperial has "achieved petroleum product sales levels not seen in decades." Meanwhile, 2019 is projected to be the second-hottest year, following 2016, worldwide since records have been kept.

The documents on Imperial's past activities suggest that the company long ago recognized the seriousness of the harm it was causing to the environment, including on the issue of climate change. Despite this knowledge, its leaders doubled down on the same damaging activities, rather than switching to a business model they knew would be necessary to avert catastrophe.

In response to The Intercept's request for comment on the archive materials, a company spokesperson said the archive documents "reflect the conversations that were happening at the time regarding the evolving science of climate change and the public policy discussions to curb emissions."

"At Imperial we have the same concerns as people everywhere -- to provide the world with needed energy while reducing GHG emissions. As noted on our website, we support the Paris Agreement as an important framework for addressing the risks of climate change and we support an economy-wide price on carbon dioxide emissions," the spokesperson added. "The company is committed to taking action on climate change by reducing its greenhouse gas emissions intensity and by supporting research that leads to technology breakthroughs."

Experts who have followed Imperial's activities over the years have noted how its rhetoric has tended to modify itself in response to public pressure.

"In the early 1990s, Imperial had to shift their behavior to accommodate high-level discussions then happening in Canada on environmental policy," said Kert Davies, the founder and director of Climate Investigations Center. "But by 1998, when that political scrutiny had eased a bit, they started going the other way and claiming that CO2 is not even a pollutant -- that it's good. As environmental activism and the threat of regulation has increased in recent years, you can now see Imperial taking a stance closer to the early 1990s, where they're saying that climate change is serious but also hedging by saying we should not do anything too extreme and also think about the economy."

"Over the decades," Davies added, "they have been adept at finding ways to delay, deny, and deflect any serious discussion about climate policy."

Return to Persagen.com